Geometry proofs build logical reasoning skills, transforming “Given” information into a proven “Prove” statement through a structured, step-by-step deductive process.

Mastering proofs isn’t guesswork; it’s applying a reliable pattern, often involving diagrams and numbered steps, to validate geometric relationships.

Study guides and interventions focus on writing proofs, emphasizing clear justifications for each statement, ultimately strengthening problem-solving abilities in geometry.

What is a Geometric Proof?

A geometric proof is a logical argument that demonstrates the truth of a geometric statement. It’s a carefully constructed series of statements, each justified by definitions, postulates, previously proven theorems, or given information.

Essentially, it’s a convincing explanation, moving from known facts to a desired conclusion. The 2-4 study guide and intervention materials highlight this process, emphasizing the need to justify each step.

Proofs aren’t simply about knowing that something is true, but why it’s true. They transform a “Given” condition into a demonstrably “Proven” result, building a solid foundation for further geometric exploration and problem-solving. This structured approach eliminates guesswork and fosters rigorous thinking.

Why are Proofs Important in Geometry?

Geometric proofs are fundamental because they develop critical thinking and logical reasoning skills – abilities extending far beyond mathematics. The 2-4 study guide and intervention resources underscore this importance, focusing on deductive reasoning.

Proofs aren’t just about finding answers; they’re about understanding why those answers are correct. They provide a rigorous justification for geometric principles, moving beyond intuition to establish certainty.

Mastering proof techniques builds a strong foundation for advanced mathematical studies and problem-solving in various disciplines. They teach precision in thought and communication, ensuring clarity and accuracy in presenting mathematical arguments. Ultimately, proofs empower you to confidently validate geometric relationships.

Key Concepts and Definitions

Essential concepts include postulates (accepted truths), theorems (proven statements), and precise definitions like congruence and bisect, vital for constructing valid geometric proofs.

Postulates and Axioms

Postulates and axioms are foundational truths accepted without proof, serving as the starting points for deductive reasoning in geometric proofs. They represent self-evident statements upon which an entire system of geometry is built.

Examples include the Segment Addition Postulate and the Angle Addition Postulate, which establish relationships between segments and angles, respectively. These postulates allow us to make logical inferences about geometric figures.

Understanding these basic assumptions is crucial because all subsequent theorems and proofs rely on their validity. They are the bedrock of geometric construction and justification, enabling a rigorous and logical approach to problem-solving.

Without clearly defined postulates, constructing a valid proof becomes impossible, as there would be no established foundation for deductive reasoning.

Theorems

Theorems are statements that have been proven true based on postulates, axioms, previously proven theorems, and logical reasoning. Unlike postulates, theorems require demonstration to establish their validity within a geometric system.

Examples include the Vertical Angles Theorem, which states that vertical angles formed by intersecting lines are congruent, and the Triangle Sum Theorem, asserting that the angles of a triangle add up to 180 degrees.

Successfully utilizing theorems in proofs involves recognizing when their conditions are met and applying them strategically to connect given information to the desired conclusion.

Mastering common theorems is essential for efficient proof writing, as they provide pre-established relationships to leverage in logical arguments.

Definitions Used in Proofs (e.g., congruent, bisect, supplementary)

Precise definitions form the foundation of geometric proofs, ensuring clarity and logical validity. Understanding terms like congruent (identical in measure and shape) and bisect (dividing into two equal parts) is crucial.

Angle relationships rely on definitions like supplementary (adding to 180 degrees) and complementary (adding to 90 degrees). Knowing these allows for manipulation of angle measures within proofs.

Definitions provide the justification for many steps, linking given information to logical deductions. Correctly applying these definitions demonstrates a solid grasp of geometric concepts.

A strong vocabulary of geometric definitions is essential for accurately interpreting problems and constructing valid proof arguments.

The Structure of a Proof

Proofs follow a logical sequence: stating the “Given” information, identifying what needs to be “Proven,” and then presenting numbered steps with justifications.

This structure ensures clarity and allows others to follow the reasoning, validating the geometric conclusion through deductive steps.

Given and Prove Statements

Establishing the foundation of any geometric proof begins with clearly defining the “Given” and “Prove” statements. The “Given” represents the known facts, the information we accept as true at the start of the problem – these are our assumptions and starting points.

Conversely, the “Prove” statement articulates the conclusion we aim to reach, the geometric relationship or statement we intend to demonstrate as true through logical deduction.

Accurately identifying both is crucial; the “Given” provides the tools, and the “Prove” defines the target. A well-defined “Prove” statement guides the entire proof process, ensuring each step contributes to reaching the desired conclusion. Without a clear “Given” and “Prove”, the proof lacks direction and validity.

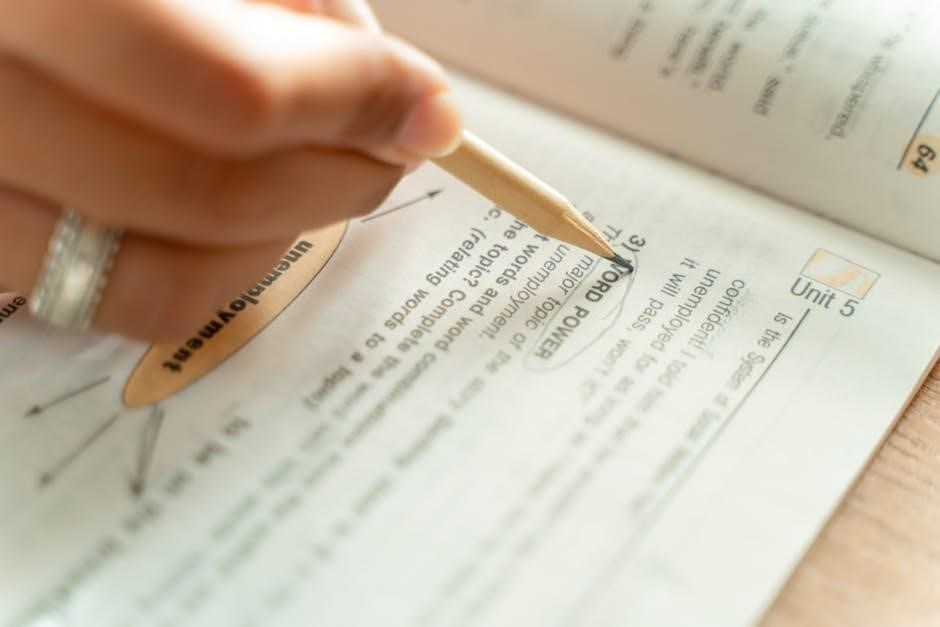

Numbering Each Step

A fundamental aspect of constructing a geometric proof is meticulously numbering each step in the logical sequence. This practice isn’t merely organizational; it’s essential for clarity and facilitates easy reference during review and verification.

Each numbered statement must be accompanied by a corresponding justification, explaining why that statement is true – referencing definitions, postulates, theorems, or previously proven statements.

Numbering allows for a clear, traceable path from the “Given” information to the “Prove” statement. It enables easy identification of any potential errors in reasoning. A well-numbered proof demonstrates a structured, logical thought process, vital for mathematical rigor and understanding.

Using Logical Reasoning

Geometric proofs fundamentally rely on deductive reasoning – moving from general truths to specific conclusions. This means each statement within a proof must logically follow from previously established statements, given information, or accepted postulates and theorems.

Avoid making assumptions; every assertion requires justification. Utilize definitions precisely, ensuring terms are applied correctly. A strong proof demonstrates a clear chain of thought, where each step builds upon the last, leading inevitably to the desired conclusion.

Logical reasoning transforms a series of statements into a convincing argument, validating the geometric relationship being proven.

Common Proof Techniques

Proofs utilize varied formats: two-column proofs with statements and reasons, paragraph proofs offering narrative explanations, and flowchart proofs visually mapping logical flow.

Two-Column Proofs

Two-column proofs are a foundational technique, organizing proof logic into distinct statements and corresponding reasons. The left column lists sequential statements – assertions about the geometric figure – while the right column provides reasons justifying each statement.

Reasons can include given information, definitions, postulates, or previously proven theorems. Each step builds upon the last, creating a clear, deductive argument. Numbering each step is crucial for clarity and tracking the logical progression.

Successfully constructing a two-column proof demands precise reasoning and accurate application of geometric principles. This method ensures every conclusion is logically supported, fostering a rigorous understanding of geometric relationships and proof construction.

Paragraph Proofs

Paragraph proofs present geometric reasoning in a narrative format, utilizing complete sentences and logical flow instead of columns. While less structured visually than two-column proofs, they still demand rigorous justification for each claim.

Effective paragraph proofs require clear transitions and precise language to connect statements and reasons. You must explicitly state the logical connections – “because,” “therefore,” “since” – to demonstrate the deductive reasoning process.

Though appearing more conversational, paragraph proofs necessitate the same level of accuracy and justification as other proof types. They emphasize the ability to articulate geometric concepts and logical arguments in a cohesive and understandable manner.

Flowchart Proofs

Flowchart proofs visually organize geometric reasoning using boxes for statements and arrows indicating the logical flow. Each box contains a statement, and below it, the justification for that statement is provided.

This method emphasizes the sequential nature of a proof, making it easier to follow the deductive reasoning process. Arrows connect statements, clearly showing how one leads to the next, often utilizing definitions, postulates, or previously proven theorems.

Flowchart proofs are particularly helpful for visualizing complex proofs with multiple steps. They offer a concise and organized representation of the logical argument, promoting clarity and understanding of the geometric relationships involved.

Essential Proof Strategies

Effective proof writing involves working backwards, identifying relevant theorems and postulates, and meticulously drawing/marking diagrams with given information for clarity.

Working Backwards from the “Prove” Statement

A powerful strategy in tackling geometric proofs is to begin with the “Prove” statement and work backwards. Instead of solely focusing on the given information, consider what conditions would need to be true to achieve the desired conclusion.

This reverse engineering approach helps identify missing links and guides the selection of appropriate theorems, postulates, or definitions. Ask yourself, “What if this were true? What would have to be true before that?”

By tracing a logical path from the end goal back to the starting point (the “Given” information), you can construct a coherent and convincing proof. This technique transforms a seemingly daunting task into a manageable series of logical steps.

Identifying Useful Theorems and Postulates

Successfully constructing geometric proofs hinges on recognizing applicable theorems and postulates. A strong understanding of these foundational elements is crucial; they serve as the building blocks of logical arguments.

When faced with a proof, actively recall relevant theorems related to angle relationships, triangle congruence (SSS, SAS, ASA, AAS), or parallel lines. Consider postulates as established truths that require no proof themselves.

Carefully analyze the “Given” and “Prove” statements to pinpoint which theorems or postulates might bridge the gap between them. A well-chosen theorem can significantly streamline the proof process, demonstrating a clear and concise path to the conclusion.

Drawing and Marking Diagrams

A clear, accurately drawn diagram is paramount when tackling geometric proofs. Begin by sketching the figure described in the “Given” information, ensuring all points, lines, and angles are represented.

Crucially, mark the diagram with the given information – congruent segments, equal angles, parallel lines – using appropriate markings like tick marks or angle symbols. This visual representation aids in identifying relationships and potential proof strategies.

Adding auxiliary lines, if necessary, can reveal hidden connections and simplify the proof. A well-labeled diagram isn’t just a visual aid; it’s an integral part of the problem-solving process, guiding logical reasoning.

Practice with Example Proofs

Strengthen proof skills by working through examples! Focus on angle relationships, triangle congruence (SSS, SAS, ASA, AAS), and proofs involving parallel lines.

Angle Relationships Proofs (e.g., Vertical Angles Theorem)

Angle relationship proofs are foundational in geometry, demonstrating how angles interact with each other. A classic example is proving the Vertical Angles Theorem – that angles formed by intersecting lines opposite each other are congruent.

These proofs often begin with given information about intersecting lines and the need to prove congruence. Utilizing postulates like the Angle Addition Postulate and definitions of supplementary angles is crucial. A two-column proof format clearly outlines statements and their justifications.

Practice involves identifying angle pairs (adjacent, supplementary, complementary, vertical) and applying relevant theorems. Diagrams should be carefully marked to visualize the relationships. Mastering these proofs builds a strong base for more complex geometric reasoning and problem-solving.

Triangle Congruence Proofs (SSS, SAS, ASA, AAS)

Triangle congruence proofs establish that two triangles are identical in shape and size. Key postulates – Side-Side-Side (SSS), Side-Angle-Side (SAS), Angle-Side-Angle (ASA), and Angle-Angle-Side (AAS) – provide the criteria for proving congruence.

These proofs require careful identification of corresponding sides and angles. Given information often includes side lengths and angle measures. A logical sequence of statements, justified by definitions, postulates, or previously proven theorems, is essential.

Successfully completing these proofs demands precise diagram marking and a clear understanding of congruence criteria. Mastering these techniques is vital for solving complex geometric problems and building a solid foundation in geometric reasoning.

Parallel Line Proofs

Proofs involving parallel lines rely heavily on theorems related to angles formed by a transversal. Alternate interior, corresponding, and same-side interior angles play crucial roles in establishing parallelism or proving relationships within figures containing parallel lines.

These proofs often begin with given information about angle measures or relationships. Justifications frequently include theorems like the Alternate Interior Angles Theorem or the Corresponding Angles Postulate. A clear, numbered sequence of statements is vital for logical flow.

Diagrams should be carefully marked with angle measures and indicators of parallel lines. Successfully navigating these proofs requires a strong grasp of angle relationships and the ability to apply relevant theorems effectively.