Addiction‚ originating in the 16th century denoting abnormal attachment‚ now presents a global public health challenge with limited therapeutic options and modest efficacy.

Understanding addiction requires acknowledging its historical evolution and modern perspectives‚ alongside its profound impact on mental health and societal vulnerabilities.

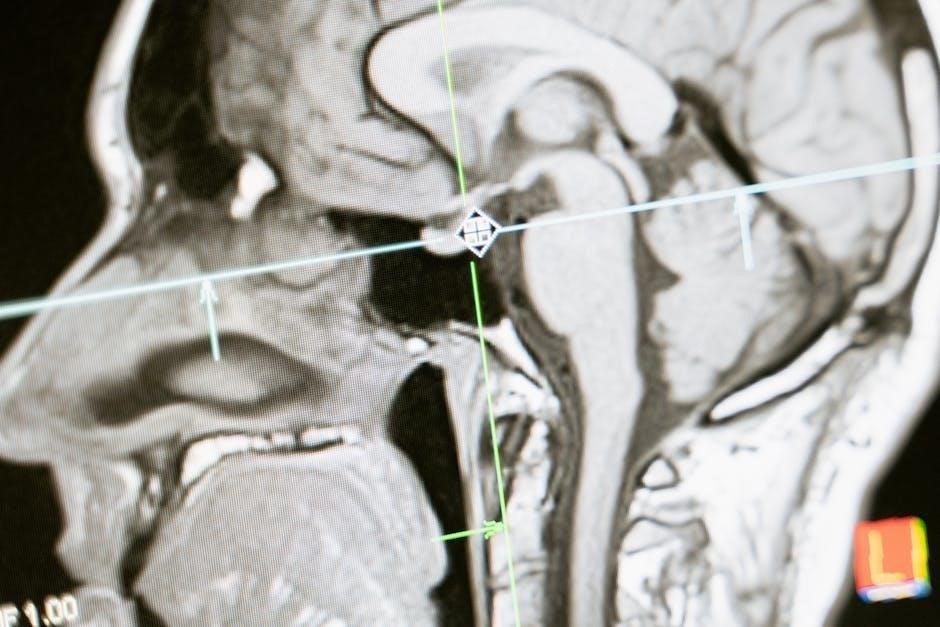

Exploring the neurobiological underpinnings of addiction is crucial‚ as it reveals how substances hijack the brain’s reward systems and alter cognitive functions.

Defining Addiction: Historical and Modern Perspectives

Historically‚ the term “addiction” emerged in the 16th century‚ signifying an abnormal attachment‚ frequently linked to alcohol consumption. Rooted in the Latin term for legally binding someone‚ it initially implied a state of being obligated or devoted to a substance or behavior. This early understanding focused primarily on the behavioral aspects‚ viewing addiction as a moral failing or a lack of willpower.

Modern perspectives‚ however‚ have dramatically shifted. Contemporary definitions‚ informed by advancements in neuroscience‚ recognize addiction as a complex brain disorder. It’s characterized by compulsive engagement in rewarding stimuli‚ despite harmful consequences. This shift acknowledges the powerful neurobiological changes that occur in the brain‚ influencing motivation‚ decision-making‚ and control.

The understanding of addiction has evolved from a moral judgment to a recognized medical condition‚ necessitating a compassionate and scientifically-grounded approach to treatment and prevention.

The Prevalence of Addiction: A Global Health Crisis

Addiction represents a significant and escalating global public health crisis‚ impacting individuals‚ families‚ and communities worldwide. Its prevalence transcends geographical boundaries‚ socioeconomic status‚ and cultural differences‚ posing a universal challenge to healthcare systems and societal well-being.

The scope of this crisis is substantial‚ with millions struggling with substance use disorders and behavioral addictions. Limited therapeutic options and modest efficacy of existing treatments further exacerbate the problem‚ leaving many without adequate care. The economic burden associated with addiction‚ including healthcare costs‚ lost productivity‚ and criminal justice expenses‚ is immense.

Addressing this crisis requires a multifaceted approach‚ encompassing prevention‚ early intervention‚ accessible treatment‚ and ongoing research to develop more effective therapies.

Neurobiological Basis of Addiction

Addiction’s core lies within the brain‚ specifically the reward pathway‚ where dopamine plays a pivotal role in reinforcing addictive behaviors and creating cravings.

The Reward Pathway: Dopamine’s Role

The reward pathway‚ a critical neural circuit‚ is central to understanding addiction’s powerful grip. Dopamine‚ a neurotransmitter‚ acts as the primary messenger in this system‚ signaling pleasure and reinforcing behaviors essential for survival – like eating and social interaction.

However‚ addictive substances dramatically hijack this pathway‚ causing a surge of dopamine far exceeding natural rewards. This intense dopamine release creates a powerful association between the substance and pleasure‚ driving compulsive seeking and use. Over time‚ the brain adapts to this artificial stimulation.

Repeated drug exposure leads to downregulation of dopamine receptors‚ meaning the brain requires more of the substance to achieve the same effect – a phenomenon known as tolerance. Simultaneously‚ the reward pathway becomes hypersensitive to drug-related cues‚ triggering intense cravings even in the absence of the drug itself. This neurobiological shift fundamentally alters the brain’s motivational hierarchy‚ prioritizing drug seeking above all else.

Brain Structures Involved in Addiction

Addiction isn’t confined to a single brain region; it’s a complex interplay across multiple structures. The Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA) initiates the reward pathway‚ releasing dopamine in response to rewarding stimuli‚ including drugs. This dopamine projects to the Nucleus Accumbens‚ the brain’s pleasure center‚ reinforcing addictive behaviors.

Critically‚ the Prefrontal Cortex‚ responsible for executive functions like decision-making and impulse control‚ is significantly impaired in addiction. Chronic drug use weakens the prefrontal cortex’s ability to regulate cravings and inhibit impulsive behaviors‚ contributing to relapse.

Beyond these core areas‚ the amygdala processes emotional memories associated with drug use‚ while the hippocampus forms contextual memories‚ linking environments with drug-seeking. These interconnected structures create a powerful neurobiological network that perpetuates the cycle of addiction‚ overriding natural inhibitory mechanisms.

The Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA)

The Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA)‚ a key component of the brain’s reward circuit‚ plays a pivotal role in the development and maintenance of addiction. This relatively small structure‚ located in the midbrain‚ contains dopamine-producing neurons that are activated by rewarding stimuli – naturally occurring‚ like food and social interaction‚ or drug-induced.

Upon activation‚ VTA neurons release dopamine into target regions‚ most notably the Nucleus Accumbens‚ signaling pleasure and reinforcing the associated behavior. Drugs of abuse powerfully hijack this system‚ causing a surge of dopamine far exceeding that produced by natural rewards.

This supraphysiological dopamine release strengthens the neural pathways connecting the VTA to the Nucleus Accumbens‚ creating a powerful learned association between the drug and pleasure‚ ultimately driving compulsive drug-seeking behavior.

The Nucleus Accumbens

The Nucleus Accumbens (NAc)‚ often described as the brain’s “reward center‚” is critically involved in motivation‚ pleasure‚ and reinforcement learning – processes profoundly disrupted in addiction. Receiving substantial dopaminergic input from the Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA)‚ the NAc integrates this signal with information from other brain regions to determine the salience and rewarding value of stimuli.

In the context of addiction‚ the NAc becomes hypersensitive to drug-related cues‚ triggering intense cravings and motivating drug-seeking behavior. Repeated drug exposure leads to long-term changes within the NAc‚ altering its structure and function.

These alterations contribute to a diminished response to natural rewards and an amplified response to drug-related stimuli‚ solidifying the cycle of addiction and increasing vulnerability to relapse.

The Prefrontal Cortex and Impulsivity

The Prefrontal Cortex (PFC)‚ responsible for executive functions like decision-making‚ impulse control‚ and planning‚ exhibits significant dysfunction in individuals with addiction. This region is crucial for evaluating consequences and inhibiting inappropriate behaviors‚ capacities severely compromised by chronic substance use.

Addiction-related changes in the PFC lead to diminished inhibitory control‚ resulting in impulsive drug-seeking despite awareness of negative consequences. Reduced activity in the PFC correlates with increased cravings and a heightened propensity for relapse‚ even after periods of abstinence.

Furthermore‚ impaired PFC function hinders the ability to adapt behavior in response to changing circumstances‚ perpetuating the compulsive nature of addiction and complicating treatment efforts.

Neurotransmitters Beyond Dopamine

While dopamine is central to the reward pathway‚ addiction profoundly impacts other neurotransmitter systems. Glutamate‚ the brain’s primary excitatory neurotransmitter‚ plays a critical role through long-term potentiation‚ strengthening synaptic connections associated with drug-related cues and memories‚ thus driving compulsive behaviors.

Conversely‚ GABA‚ the main inhibitory neurotransmitter‚ experiences disruption‚ leading to diminished inhibitory control. This imbalance contributes to impulsivity and increased vulnerability to relapse; The interplay between glutamate and GABA is crucial for maintaining a healthy balance in brain activity.

Understanding these broader neurochemical changes is vital for developing more targeted and effective addiction treatments‚ moving beyond solely focusing on dopamine modulation.

Glutamate and Long-Term Potentiation

Glutamate‚ the brain’s most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter‚ is fundamentally involved in synaptic plasticity‚ particularly through a process called long-term potentiation (LTP). In addiction‚ LTP strengthens the connections between neurons that respond to drug-related cues – sights‚ sounds‚ or environments – associating them with the rewarding effects of the substance.

This strengthening isn’t merely associative; it creates powerful‚ ingrained memories that drive craving and compulsive drug-seeking behavior. Repeated drug exposure dramatically enhances LTP in key brain regions‚ making these cues incredibly salient and difficult to ignore.

Essentially‚ the brain learns to anticipate and intensely desire the drug‚ even in the absence of the substance itself‚ due to glutamate-mediated LTP.

GABA and Inhibitory Control

Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain‚ playing a critical role in regulating neuronal excitability and maintaining balance. Addiction often disrupts GABAergic neurotransmission‚ leading to diminished inhibitory control and increased impulsivity – key features of addictive behaviors.

Chronic drug use can downregulate GABA receptors‚ reducing the brain’s ability to dampen excitatory signals. This imbalance contributes to heightened sensitivity to rewarding stimuli and a decreased capacity to resist cravings.

Alcohol‚ specifically‚ directly enhances GABAergic neurotransmission‚ initially producing calming effects‚ but long-term use leads to adaptive changes that ultimately impair GABA function and contribute to withdrawal symptoms and continued dependence.

How Addiction Changes the Brain

Chronic drug exposure induces significant structural and functional alterations within the brain‚ impacting gray and white matter integrity and overall brain activity patterns.

Structural Changes: Gray Matter and White Matter

Prolonged substance use demonstrably alters the brain’s physical structure‚ affecting both gray matter – responsible for processing information – and white matter – facilitating communication between brain regions.

Studies reveal reductions in gray matter volume in key areas like the prefrontal cortex‚ crucial for decision-making and impulse control‚ and the anterior cingulate cortex‚ involved in regulating emotions and behavior.

White matter tracts‚ the brain’s communication networks‚ also experience changes‚ exhibiting reduced integrity and efficiency. These alterations disrupt the flow of information‚ contributing to impaired cognitive function and increased vulnerability to relapse.

The specific patterns of structural change vary depending on the substance used and the duration of addiction‚ but consistently demonstrate the neurotoxic effects of chronic drug exposure. These changes aren’t always permanent‚ with some recovery possible through abstinence and therapeutic interventions‚ but can be substantial.

Functional Changes: Altered Brain Activity

Beyond structural alterations‚ addiction profoundly impacts how the brain functions‚ leading to measurable changes in brain activity even in the absence of drug exposure. Neuroimaging studies consistently demonstrate reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex‚ impairing executive functions like planning‚ decision-making‚ and self-control.

Conversely‚ heightened activity is often observed in reward-related brain regions‚ such as the nucleus accumbens‚ contributing to intense cravings and compulsive drug-seeking behavior. This imbalance reinforces the addictive cycle.

These functional changes extend to altered connectivity between brain regions‚ disrupting communication and contributing to cognitive deficits. The brain becomes increasingly focused on obtaining and using the substance‚ at the expense of other important functions.

These alterations contribute to the loss of control characteristic of addiction and increase vulnerability to relapse‚ even after prolonged periods of abstinence;

Impact of Chronic Drug Exposure

Prolonged substance use triggers a cascade of neuroadaptations‚ fundamentally reshaping brain function and structure. Chronic exposure overwhelms the brain’s natural reward pathways‚ leading to downregulation of dopamine receptors and reduced sensitivity to natural rewards like food or social interaction.

This diminished responsiveness contributes to anhedonia – the inability to experience pleasure – and fuels the relentless pursuit of the drug. Simultaneously‚ the brain attempts to compensate for the constant stimulation‚ resulting in tolerance and the need for increasing doses to achieve the desired effect.

These adaptations aren’t limited to reward circuitry; they extend to stress response systems‚ increasing vulnerability to anxiety‚ depression‚ and other mental health disorders. Ultimately‚ chronic drug exposure compromises the brain’s ability to function optimally.

Specific Substances and Their Effects on the Brain

Distinct substances exert unique effects‚ like cocaine impacting the dopamine transporter‚ opioids hijacking the endorphin system‚ and alcohol modulating GABAergic neurotransmission.

These interactions profoundly alter brain chemistry and circuitry‚ driving compulsive drug-seeking behavior and contributing to addiction’s complex nature.

Cocaine and the Dopamine Transporter

Cocaine’s potent effects stem from its interaction with the dopamine transporter (DAT)‚ a crucial protein responsible for clearing dopamine from the synaptic cleft – the space between neurons.

Normally‚ dopamine is released during rewarding experiences‚ signaling pleasure and motivation‚ and then quickly recycled by DAT. Cocaine competitively binds to DAT‚ effectively blocking dopamine reuptake.

This blockage leads to an accumulation of dopamine in the synapse‚ resulting in an amplified and prolonged dopamine signal. This surge of dopamine overwhelms the reward pathway‚ creating an intense euphoric sensation.

Repeated cocaine use desensitizes dopamine receptors and alters DAT function‚ diminishing the brain’s natural reward response and driving compulsive drug-seeking behavior.

The brain adapts to the artificially elevated dopamine levels‚ requiring increasing amounts of cocaine to achieve the same effect – a hallmark of tolerance and addiction. Furthermore‚ this disruption contributes to cravings and relapse vulnerability.

Opioids and the Endorphin System

Opioids‚ including heroin‚ morphine‚ and prescription pain relievers‚ exert their addictive effects by mimicking the action of naturally occurring endorphins – neurotransmitters involved in pain relief and pleasure.

Endorphins bind to opioid receptors in the brain‚ reducing pain perception and inducing feelings of well-being. Opioids also bind to these receptors‚ but with a much stronger and more prolonged effect.

This intense activation of opioid receptors floods the brain with dopamine‚ reinforcing drug-taking behavior and creating a powerful reward signal. Over time‚ the brain reduces its own endorphin production.

Consequently‚ individuals develop tolerance‚ requiring higher doses of opioids to achieve the same analgesic or euphoric effects. Withdrawal symptoms‚ characterized by pain and discomfort‚ further drive compulsive drug use.

The disruption of the endorphin system contributes to the chronic‚ relapsing nature of opioid addiction and underscores the need for comprehensive treatment strategies.

Alcohol and GABAergic Neurotransmission

Alcohol profoundly impacts the central nervous system‚ primarily by enhancing the effects of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)‚ the brain’s primary inhibitory neurotransmitter.

GABA reduces neuronal excitability‚ promoting relaxation and reducing anxiety. Alcohol binds to GABA receptors‚ amplifying GABA’s inhibitory actions and leading to sedative and anxiolytic effects.

This initial calming effect contributes to alcohol’s reinforcing properties‚ but chronic alcohol exposure leads to significant neuroadaptations within the GABAergic system.

The brain attempts to counteract the constant inhibition by reducing GABA receptor sensitivity and increasing glutamate activity‚ resulting in tolerance and withdrawal symptoms.

Withdrawal manifests as anxiety‚ agitation‚ and‚ in severe cases‚ seizures‚ driving continued alcohol consumption to alleviate these unpleasant effects and maintain homeostasis.

Addiction‚ Mental Health‚ and Social Status

Addiction frequently co-occurs with psychiatric disorders‚ and social status profoundly impacts mental wellbeing‚ creating vulnerabilities and influencing addiction pathways.

These interconnected factors demand holistic understanding.

The Link Between Addiction and Psychiatric Disorders

Comorbidity‚ the simultaneous presence of addiction and mental health disorders‚ is remarkably common‚ significantly complicating both diagnosis and treatment. Individuals struggling with conditions like depression‚ anxiety‚ bipolar disorder‚ or schizophrenia exhibit substantially higher rates of substance use disorders‚ and vice versa.

This isn’t merely coincidence; shared neurobiological vulnerabilities underpin this connection. Dysregulation within the brain’s reward pathway‚ particularly dopamine signaling‚ is implicated in both addiction and mood disorders. Furthermore‚ genetic predispositions can increase susceptibility to both types of conditions.

Self-medication is often a contributing factor‚ where individuals attempt to alleviate distressing psychiatric symptoms through substance use‚ inadvertently exacerbating their overall condition. Addressing both disorders concurrently – integrated treatment – is crucial for improved outcomes‚ rather than treating them as separate entities. Ignoring one condition while focusing on the other often leads to relapse and continued suffering.

Social Determinants of Addiction Vulnerability

Addiction isn’t solely a matter of individual willpower; a complex interplay of social factors significantly influences vulnerability. These “social determinants” encompass economic instability‚ lack of access to healthcare‚ educational disparities‚ and systemic inequalities. Individuals facing poverty‚ discrimination‚ or limited opportunities are disproportionately affected by substance use disorders.

Exposure to trauma‚ particularly during childhood‚ is a potent risk factor‚ altering brain development and increasing susceptibility to addiction later in life. Furthermore‚ social isolation and lack of supportive community networks can exacerbate feelings of hopelessness and contribute to substance use as a coping mechanism.

Addressing these broader societal issues is paramount in preventing and treating addiction. Public health initiatives must focus on creating equitable access to resources‚ fostering supportive communities‚ and dismantling systemic barriers that perpetuate vulnerability. Ignoring these factors limits the effectiveness of individual-focused interventions.

Emerging Therapies and Research

GLP-1s demonstrate potential for ameliorating psychiatric and neurologic symptoms‚ prompting clinical trials exploring their efficacy in addiction treatment and recovery support.

GLP-1s and Potential for Addiction Treatment

Emerging research suggests a surprising link between medications initially developed for type 2 diabetes – GLP-1 receptor agonists – and a potential reduction in addictive behaviors. These drugs‚ like semaglutide and liraglutide‚ are known for their effects on appetite and blood sugar control‚ but recent studies indicate they may also influence brain pathways involved in reward and craving.

Evidence suggests GLP-1s can ameliorate psychiatric and neurologic symptoms often co-occurring with addiction‚ such as depression and anxiety. This is particularly significant given the high rates of comorbidity between substance use disorders and mental health conditions. The mechanism isn’t fully understood‚ but it’s hypothesized that GLP-1s may modulate dopamine signaling‚ reducing the reinforcing effects of drugs and alcohol.

More clinical trials are crucial to determine the efficacy and safety of GLP-1s as an addiction treatment. While preliminary findings are promising‚ larger‚ controlled studies are needed to confirm these effects and identify which patient populations might benefit most from this novel therapeutic approach. This represents a potentially groundbreaking shift in addiction treatment paradigms.

Future Directions in Addiction Neuroscience

Addiction neuroscience is rapidly evolving‚ demanding continued investigation into the complex interplay between brain function‚ genetics‚ and environmental factors. A key area of focus is personalized medicine – tailoring treatment strategies based on an individual’s unique neurobiological profile and addiction history. Advanced neuroimaging techniques‚ like fMRI and PET scans‚ will play a crucial role in identifying biomarkers predictive of treatment response.

Further research is needed to fully elucidate the role of specific neurotransmitters beyond dopamine‚ including glutamate and GABA‚ in the development and maintenance of addiction. Understanding these complex interactions will pave the way for more targeted pharmacological interventions. Exploring the impact of chronic drug exposure on brain plasticity and the potential for neurorestorative therapies is also paramount.

Ultimately‚ a comprehensive approach integrating neuroscience‚ psychology‚ and social sciences is essential for developing effective prevention and treatment strategies.